Agridirect.ie discusses the menace of Johne’s disease and outlines some measure that farmers should take to prevent the spread of this insidious infection.

Johne’s disease: what is it?

Johne’s disease is one of the most frustrating and insidious diseases that any farmer will have to deal with. Many other infectious diseases that target the digestive system, such as winter dysentery and stomach worms, are a nuisance that cause damage to a cow’s digestive health; but these are relatively unlikely to kill the animal. In stark contrast, once contracted Johne’s disease will eventually cause death in most cases.

Johne’s disease is an infection caused by paratuberculosis, a subspecies of Mycobacterium avium. As its name suggests, paratuberculosis is a close relative of the infectious organism that causes TB (tuberculosis). This relationship should give the uninformed some indication of the severity of the disease. Paratuberculosis targets the intestines of infected animals, causing chronic diarrhoea, weight loss and infertility. The animal will rarely recover from these symptoms and ultimately death is only a matter of time.

Johne’s disease is commonly attested in beef herds, where it causes enormous revenue loss because infected animals cannot make weight targets. However, the infection is perhaps most associated with the dairy herd. A dairy cow that has been infected with Johne’s disease will yield significantly less milk. The real difficulty here is that paratuberculosis will diminish an animal’s milk yield long before she exhibits any other symptoms of the disease. This can make Johne’s disease difficult for farmers to diagnose even as it is doing enormous damage to their revenue prospects.

Clinical signs of Johne’s disease

After an animal becomes infected with paratuberculosis, it can take years for the first symptoms to show. Because the disease is not immediately manifest, blood tests offer the only way to confirm its presence in the early stages of infection. There is a problem here, too, since tests are not 100% accurate and can fail to detect the presence of paratuberculosis. Nonetheless, blood tests are the best tool we have for early detection of the disease and it is a good idea to get your entire herd tested regularly.

Usually, the clinical signs of Johne’s disease begin to show in animals older than three years. Dairy farmers often attest to an initial period of steady reduction in milk yields or a failure to hold to the bull, before the symptoms of advanced disease set in.

The symptoms of advanced Johne’s disease are well known to many farmers. The animal becomes emaciated despite access to plenty of good quality feed, and is constantly afflicted by persistent and severe diarrhoea. At this advanced stage of illness, dung samples will usually show the presence of the paratuberculosis microorganism.

Infectiousness

Aside from being a fatal illness in its own right, Johne’s disease also leaves cattle susceptible to a wide range of other ailments including mastitis and pneumonia. The disease is also highly infectious and, once it is in the herd, it will spread quickly. Therefore, it is essential that all farmers take precautions against introducing it in the first place. A few simple precautions could help to reduce revenue and production losses and increase the overall value of your herd.

Control and prevention

First of all, you should test regularly for Johne’s disease in your herd. Even if you do not believe that the disease is present on your farm, an annual blood test can do no harm. If you have had a negative blood test in the last year, but are now seeing the symptoms of Johne’s in your herd, you should have the suspect cases tested individually.

In most cases, Johne’s disease is brought onto the farm by imported cattle. Therefore, it is best to maintain a closed herd. Instead of buying in replacement heifers, try to replace cull cows with animals born on your own farm. Where this is not possible, make a concerted effort to purchase cows from herds that have been regularly screened for paratuberculosis.

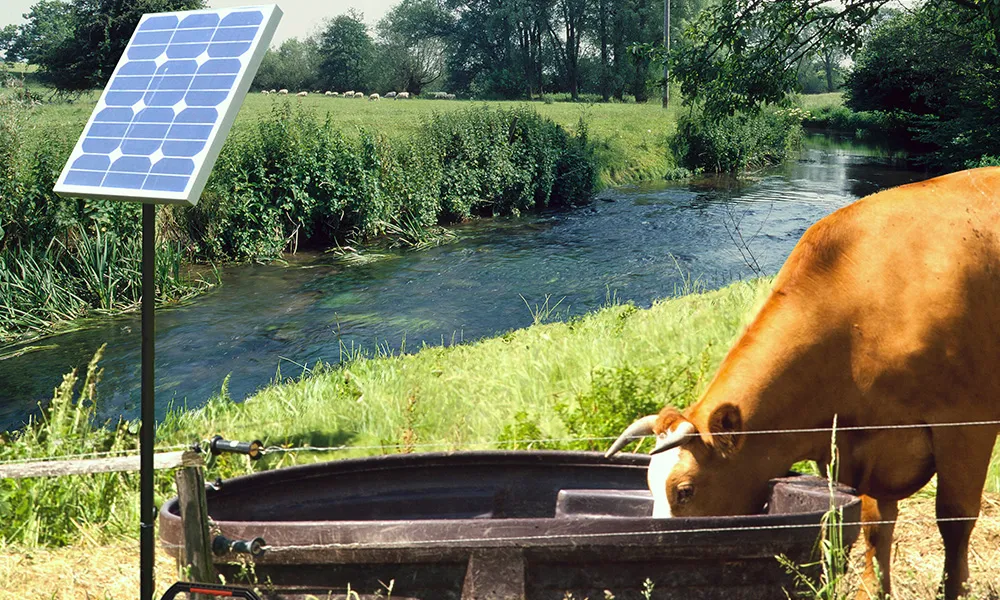

Fence water sources

Johne’s Disease is also known to spread via contaminated water. If possible, you should ensure that your herd has access to mains drinking water. If this is not an option for you, and your cattle are drinking from a well or other private water source, you need to have this source tested regularly for paratuberculosis. You should fence off stagnant water sources, such as ponds, because these are a perfect hiding spot for this organism.

And finally, remember that paratuberculosis and other infectious diseases tend to lie on slurry and dung. To prevent infection via manure, do not graze young animals on slurry/dung fertilised land for at least 6 months after application. This applies to sheep as well as cattle. While Johne’s disease is commonly associated with cattle, sheep are also highly susceptible to infection and need to be protected.