Agridirect discusses the future of Irish farming with author Ryan Dennis. Ryan Dennis, author of new agricultural novel The Beasts They Turned Away, hails from a farming family in upstate New York. Long before he was a published writer, Ryan learned how to manage a dairy herd. In his own words, “I am the 4th generation in my family to milk cows”. It is also likely that his will be the last generation of the family to work the milk parlour.

The Dennis family stopped milking cows in 2014, at a point when farm gate prices had cratered so badly that “500 cow dairies weren’t breaking even”. It was the inevitable outcome of decades of productionist agricultural policy that has decimated the family farm in the United States.

Having spent several years studying Irish and EU agricultural policy at NUI Galway, Ryan fears that small Irish farms may suffer a similar fate. In this interview, he talks to us about global agricultural policies, and discusses how Irish policymakers can avoid sacrificing the family farm “at the altar of the free market”. Ryan also tells us about his debut novel, The Beasts They Turned Away, a story set on an Irish farm and which focusses on the real lived experience of farming. (Our interview with Ryan Dennis is available below in both video and transcript forms. The transcript has been edited as appropriate.) Participants: Ryan Dennis (RD) Agridirect Interviewer, Micheál Geoghegan (I)

I: Ryan, could you tell me a little bit about your farming background in New York State, about your family’s farm and what happened to it?

RD: I was the 4th generation of my family to milk cows. Our farm trajectory probably followed the same path as a lot of farms in the area at the time. My adolescence was mostly covered by the 90s and in the US farming was good in the 90s. You know, I think there were jokes about all the money that farmers were making, but those jokes would be followed by a wink and a nod. If farming was hard, it was only in the way that it’s naturally hard, that’s inherent in the act itself.

Then, probably towards the end of the 90s, you felt this shift in farming […]. You saw lower farm gate prices and higher costs added to that. So on our farm we had 100 cows in a stanchion barn in the 90s, because that’s what everyone had and that’s what you needed to make a living. And then by the early 2000s we’d doubled the herd to 200, to a free stall operation with a double herringbone parlour, because that’s what you needed to do to stay alive.

The US, at that point, was already well on the productionist treadmill that the economist Willard Cochrane named, whereby once farms are encouraged to expand then there’s more milk in the market. As a result, the farm gate price lowers and you have to expand again to make the same margin. And so that kept continuing and it got to the point where, when our family stopped milking cows in 2014, 500 cow dairies weren’t breaking even. Where our farm was starting to go backwards in numbers for a while and it just became impossible to compete. So at the moment the whole area has consolidated into two farms that have well over 1,000 cows each. My understanding is that that’s the minimum to break even at this point in the United States.

I: So what we’re talking about here is the concentration of agriculture in a very small number of hands. I think we see something similar in Brazil. Is that the sort of direction you think the US is going in?

RD: Yeah, I’d sadly (probably) declare the family farm dead in the United States. I think it’s gone too far and I don’t think the right type of will and knowledge and procedures are there to resuscitate it. I’d say the country that went quicker and more extreme in the same manner as the US is Australia where, in 2000, they decided they wanted to be a completely deregulated industry. Within a couple of years, in some areas, people lost two thirds of their farms. The change was very sudden and very abrupt. So in the US it’s not entirely deregulated but it’s increasingly deregulated. And there hasn’t been a will to put mechanisms in place to halt expansion or to make it more profitable for a small farm to exist. So at this point, yeah, there is going to be no one left in the industry with less than 1,000 cows at this point unfortunately.

I: OK. And you don’t see the Biden administration changing direction? Has there been anything, in terms of his decisions or picks in cabinet, that might lead you to think that there will be a change in direction? Or will it continue to go in the direction you’ve described?

RD: It’s funny. Whenever a Republican is in office in the United States, agriculture policy is easy because they believe in the free market, that the free market works and you don’t need any sort of government intervention. Then when a Democrat takes office they say “alright, what do we need to do to try to make a liveable income for farmers?”

So I believe Vilsac, the secretary of Ag, is the only one serving two terms that aren’t back to back in US history. He’s been given a second chance to save his name in Ag policy because his first terms was fairly uneventful. I believe that they are looking at ways to reward land going into grass-based production and things that look good environmentally. But I think the problem is that it’s going to take something extremely radical in the United States to make a farm of 100 cows profitable again. I think we’ve just gone too far towards expansion and it’s going to take something big to reverse that and it’ll be costly initially for the government, which I think also lessens the will.

And yeah, I see that unfortunately it’s a bit too late. Some people say that the true fight to save family farms in America was in 1963, under the JFK administration. At that time big agri-industry business was just starting to take off in the 50s when Cochran (the economist I mentioned before) was thinking about Ag policy. Technology was just starting to take off and he saw that without something that protects profitability for the small farm and limits expansion, it’s going to be a race to the bottom. You’ll have to keep getting bigger and bigger and bigger, and the price you receive is going to be lower and lower and lower. And so he (Cochran) tried to enact supply control. JFK was behind him; but of course he was called a Communist, which is the easy slur in America because the Cold War was still raging on. If you expressed any idea that wasn’t praising the free market, it meant you were obviously an agent for the USSR.

So since then, American farm policy has largely been sacrificed at the altar of the free market and I think farmers themselves, or anyone who is even vaguely familiar with the act of farming, could probably guess why agricultural policy doesn’t work for the free market. Take dairy farming for example. Milk is a flow product, you can’t stop making milk. It’s also a perishable product, so other than turning it into powder you can’t really store it. And because of that, farmers don’t have the same countervailing agency in the market that retailers and processors do. So the free market is never going to be a friend of the farmer. Agriculture simply can’t be regulated by the free market alone.

I: Absolutely, I couldn’t agree more. So obviously you’ve given a fairly comprehensive account of the history of American policy in terms of agriculture. Now there is a different way, of course. I’ve done a bit of reading on your life and your experience. You have lived in Iceland which, as far as I can gather, provides a very different model to the direction that these big countries like Australia and the US are going in. Could you maybe talk a little bit about your experience in Iceland?

RD: I applied for a Fullbright to go and write about Icelandic farmers. The pitch I used to present my project to the Fullbright board was the same one I used to apply in previous years, which was “Hey listen, your farmers are struggling, so you need me to go and write about it while there’s still time.” However, when I arrived in Iceland I found out that they didn’t need me to write about their farmers. They weren’t struggling. It’s probably to my mind the only developed nation where a farm of 60 cows can support a family and support it well. So Iceland stands as proof that supply control can work, that it is possible to support agriculture in a way that prioritises farmer income and the lived experience of farmers. So yeah, since 1984 Iceland has had milk quotas and they have subsidized their farmers, particularly more in the last decade or two.

And as anywhere that Ag policy exists, it’s not without controversy. There are always some people saying “why should we pay a little bit more for our farm products or why should we subsidise farmers?” But by and large the public is behind it. You know as part of the deal to support Icelandic agriculture, the cows have to be on pasture so many weeks of the year as well, which kinda fits in with what the public wants of their agriculture, and the idea of it. But yeah, Iceland has been a sort of anthem call in my understanding of ag policy in that it’s proof that these things do work, that it can be successful. I mean granted Iceland is a small nation, they’re more agricultural than other nations and their general population is more closely connected to agriculture than most other places in the developed world. But it was a bit of a justification for myself and I think for other people who are proponents of supporting the small farm.

I: So obviously that’s really interesting. You’ve talked about Iceland, a small country, and the US, a huge country. Ireland is bigger than Iceland, but much smaller than the US. What’s your take on Irish agriculture and the direction that it’s going in? RD: I’d say first to talk about Irish and EU agriculture, to put it in a global perspective, I think the EU does a lot more for the farmer than other major agricultural communities such as the US and Australia.

There is a concern for the experience of the farmer, supporting small and mid-size farms is always a part of the conversation. So in that way, globally, I myself have a lot of respect for some of the EU policy.

However, having said that, I think ever since the McSharry reforms in 92, when the EU started shifting more towards a market-oriented pricing for its farm gate pricing, it started going in a direction that ultimately is detrimental to family farming.

The biggest event in that has been the phased removal of milk quotas. I know that a lot of farmers supported the removal of milk quotas, and I think I understand that. I grew up on a farm myself, I understand that when you’re doing the same act every day, you’re milking cows, you’re feeding them, you’re doing it again and you’re thinking “ahh if I could have just 15 more cows it would mean this much more money and then it would be better, if I could expand just a little bit more like this.” So I can understand the farmers’ support for that; but I also think agricultural industries are very short-sighted.

All the EU had to do was look at what happened in the United States without supply control. Look what happened in Australia and what the consequences were for those farmers, what farming looked like after that. So I am a bit concerned that the Irish farmers are going to have to keep expanding and expanding and competing directly with other EU farmers. I don’t think ultimately Ireland can expand as much as some of the countries on the eastern side of the EU that previously had collective farms. Like in east Germany, I believe there are still some collective farms after socialism.

You know, land is quite limited in Ireland as well, so I think […] there’s going to be a continual structural change in Irish agriculture in particular. I wonder if it might hit a point where it can no longer expand based on grass-based systems, so it’s going to be more concentrate-fed like in the US, like other places.

The style of farming is going to change. And it’s going to be a different experience for Irish farmers, it’s going to be a different type of farming. So I lamented that type of ideology within the CAP policy and another thing I don’t think always gets mentioned is that there’s not always the type of leadership in these situations, I think, that one might expect.

In particular, farmers look to agricultural journals for leadership, but also for what’s happening. There’s one in every country. And you know farmers are always going to pick up agricultural journals and look to them for guidance on what they should hope the future should look like and what kind of ag policy they should support. Well these types of journals and media sources, they’re making a living from the farmers themselves, from the subscriptions, and I think sometimes they’re victims to telling the farmers what they want to hear. So, you know, I think there are different places you can trace back to American history where these journals told farmers: “you have to expand, and no you don’t want supply control”, because that’s what the farmers wanted to hear.

And in Ireland as well, there were major journals that, back when the quotas were being discussed, and there was consideration about whether they should be removed or not, they stood up and said: “no, we support the phased removal of quotas.” Because that’s what the farmers wanted themselves and now I think some of these journals are saying: “yeah, we need some quotas back on” or something of the sorts. In any case, I think there’s a vacuum of a trustworthy voice in these things.

I: I guess that’s capitalism in a way too, isn’t it? You’re always inclined to give the consumer what they want, rather than provide that dose of reality when it’s timely. What can the Irish government do, alone, outside of EU policy? Are there any measures that the Irish government can enact to protect Irish agriculture from going in the direction you’re describing?

RD: Well first, I’m aware of my position of not being Irish and coming in and speaking of Irish politics, so I’d recognize that and I don’t mean to be someone coming in with all the answers or to suggest that.

One thing I would consider perhaps is lowering the cap on the basic scheme. I believe, am I right, that the cap is at €150,000? So whenever subsidies are discussed in the media, they’re usually positioned wrong. Usually it’s a “should we have them or shouldn’t we have them?” type of debate.

Really I think it’s more appropriate to say: how can we use them effectively?

One of the ways that you can use them effectively is to put a hard cap on the amount a single farming enterprise can receive, to make sure that that the smaller farmers are receiving a larger percentage of their income through these subsidies than larger farms are, or at least are supported more by it. I think that saves taxpayers’ money as well; and it gives more advantage to small farmers and encourages people to stay small.

Farmers who expand aren’t bad people of course, but every farmer would agree that they’d rather make a good living with 30 cows than make the same living on 300 cows. So I would consider maybe lowering the cap, which I think at the moment is under the purview of the Irish government.

I’ve often wondered if it would be possible to have the government invest in a co-op in a value-added chain, where consumers can buy milk from only small farms. It could be a structural and logistically tough thing to accomplish, but I think […] the public has the will to support small agriculture. I think people would be willing to pay a little more if they knew the money was going to the type of farm they see on TV, with happy cows and everything.

But at the moment, there isn’t a bridge between people’s support for small agriculture and a way that they can actually act on that. A government sponsored co-op that creates products made from produce from small agriculture instead of on a major, large scale (could provide that bridge).

I: Really interesting idea, thanks Ryan. So I suppose we’ve covered quite a bit of policy stuff there. So I do want to move on and talk a little bit about the novel. Congratulations by the way, a huge achievement. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about what the novel is about, and the inspiration for it; and indeed how the narrative links in with your own farming experience.

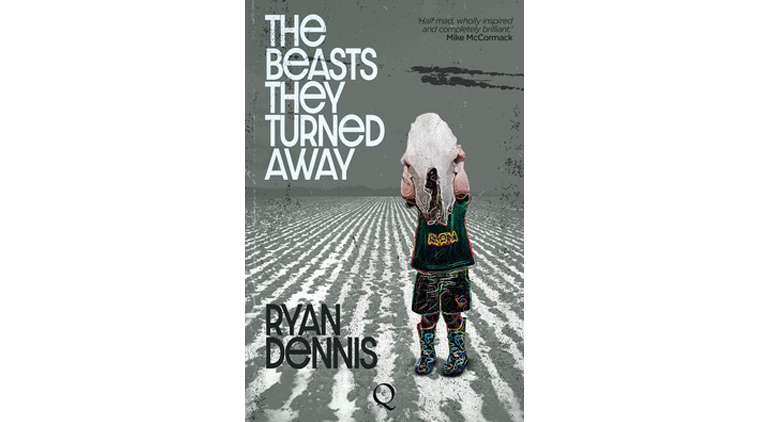

RD: Sure. The novel is titled The Beasts They Turned Away.

Growing up on a farm, I’ve noticed that there aren’t a lot of stories written about farmers anymore, and the amount of movies about farmers is less still. There aren’t a lot of opportunities for farmers to see their own experiences reflected back to them in the things they watch and read. And I’d always thought that was unfair to a group of people who had a lot of selfhood, who worked hard and struggled and gave quite a bit back to society. So I’ve always had an interest in trying to tell the story of people like my family, who are farmers and try to make a living out of it.

So at first, of course, I was writing in a US context; and when I came to Ireland to do a PhD and to study EU agricultural policy, it was a chance for me to write about agriculture in an Irish context, which in some ways is a similar story. There are similar forces at work, but a whole new set of details and circumstances and language that made the act of trying to write the story fresh for me, and exciting.

So in the novel itself, an aging Irish farmer, Íosac Mulgannon, is starting to lose his sanity and he is fighting to hold onto his farm as well as take care of a small child in his possession. The child is mute, potentially cursed, and wears a cow skull over his head most of the time. It was a bit tricky getting it published, because the larger publishers are concerned about marketability, as are agents. They thought it was too non-conventional in style. It’s not an easily digestible story of “down-on-the-farm” or anything. And I think some of the more literary circles were a bit wary of all the intimate farming details. But it finally found a good publisher that believed in it and it was published last month.

The reviews have all been good and it seems to be doing well so far anyway, as far as I can tell.

I: Brilliant, I’ve just ordered a copy so I’m hoping I’ll get it by next week and I can crack on with it. Really looking forward to reading it. Definitely it is true, what you say about the number of novels that are set on a farm, and it is striking that you don’t really encounter many where the act of farming is described in detail – not even in the novels of the great Irish rural writer John McGahern. Obviously most of his writing was set on a farm, and yet we don’t see that much of the act of farming in his work. Are there any other writers who deal with agriculture in that way, describing the physical act?

RD: Eugene McCabe was also a farmer writer from up in Monaghan, in Clones. I think some of his work had some specific acts of farming. I think Death of Nightingales and some of the short stories in particular deal with farming. Belinda McKeon’s Solace published in 2011 was the last Irish novel to really have a bit of farming in it. And McGahern’s That They May Face the Rising Sun probably has the most farming in it of anything, and scholars never bother to talk about the farming in it. And Donal Ryan, who is now considered kind of a rural chronicler. Farming is very sparse in his work as well. So you’re right, there’s quite a thinning and a quieting of work that deals with agriculture.

I: Why do you think that is? Why do you think that writers are sort of shying away from really engaging with the physical act of farming?

RD: I think the easiest part of that answer is the fact that as there are fewer people involved in agriculture, there are fewer people with intimate knowledge of it. But also, at least in the American context, and I fear that this may eventually happen in the Irish context, it may be that the type of farming that exists nowadays might not be […] a sexy place to set a story. To my knowledge there haven’t been any novels set on a thousand cow dairy farm.

So yeah, I think maybe in some ways the death of the farm novel tells us something about ourselves, and what we ultimately think about the way agriculture is heading and maybe our fear of where it’s heading.

I: On that note, I think it’s a good place to talk about the Milk House. Can you talk a bit about what the Milk House is and what the objective is?

RD: Sure. For the last ten years I’ve written a column called the Milk House, which was syndicated in a few print journals. But as of a little more than a year ago, I recreated it into an online space where those who write on rural subjects, whatever they may be, can find people who like reading about rural subjects.

I think there’s a bit of a misnomer that the best and most exciting writing has to come out of the metropolitan areas, where there is some exciting work being done by those writing from and for the countryside. And I created the Milk House as a space both for those writers to find new audiences, and also to prove that the experience of those in rural areas is, I suppose, universal.

There are certain elements that someone in rural Ireland can relate to in rural Japan. But also because (rural life) is very unique and dynamic, it’s something that deserves close attention in writing and in literature. That’s what it hopes to be about anyway.

I: It’s a really interesting idea. I think having grown up in Leitirm, the most rural county in Ireland, you get a sense sometimes that people in the cities take a slightly condescending attitude towards rural people. I definitely feel that that is shared. I don’t know if it’s a global thing, but for sure I’ve observed it in the countries that I’ve been in. Is it the same in the states?

RD: Yeah, absolutely, and I think one thing that happens is that the experience of rural people has the edges rounded off, or gets lumped into a big group, you know. Perhaps in an American context it’s become quite clear of late, during the Trump campaign, that he did receive a lot of support from rural areas; but there is still a considerable percentage of people living there who said: “wait a minute, that doesn’t represent me, that’s not who I am”.

So I think those examples reinforce to me that there are individual voices to be heard in the countryside and they’re worth exploring. They can’t all be put in one box.

I: And again sometimes with the Trump phenomenon, and similar phenomena across the globe, I wonder if the support in rural areas for these figures, who seem to come from outside the political establishment, is a reaction from demographics who feel they have been left behind by social, political and economic developments.

RD: I 100% agree. I didn’t realise how poor rural America was until I lived in parts of Europe and saw rural life there. And then coming back I had a sort of reference point to where I grew up and the things I could see around me. Rural America has certainly been left behind and is impoverished and doesn’t have access to the resources and education and the things that urban areas do. So I agree that a large part of what we saw was probably a response to that.

I: Do you know of any writers who are capturing that essence in their writing or that phenomenon, through the Milk House?

RD: I can’t think off the top of my head. So far a lot of our contributors have been Irish and English. Some Americans but a lot of Irish and English.

I: How many contributors have you had at the Milk House at this stage?

RD: We run a different one nearly every week, so we’ve had between 40 and 50 different contributors. Some have contributed twice as well, so 40 something contributors.

Interviewer’s note: sincere thanks to Ryan Dennis from all of us here at Agridirect. Ryan is a real gentleman and was very generous with his time and knowledge. His novel, The Beasts They Turned Away, is available for purchase online from numerous Irish bookstores. For more information on Ryan’s projects, visit https://www.themilkhouse.org/ryan-dennis/ or http://penofryandennis.com/ MPG