Teagasc data

Recent data from Teagasc indicates that, at present, just 20% of calves on Irish suckler farms are bred from Artificial Insemination (AI). In some ways this paltry figure is surprising. At a time when genetic progress is viewed as key to sustaining the national herd, AI offers access to the best genetics across a variety of breeds, both replacement and terminal. Use of AI, therefore, is viewed as essential to achieving desirable stock traits in a sector faced with an unpalatable choice between radical change and gradual decline.

Farmers reluctant?

That is not to say that the widespread reluctance to embrace AI is without cause. Farmers are justifiably wary of overreliance on AI, with many viewing it as inefficient and labour intensive. In the absence of a bull, heat detection and timely insemination become additional headaches that already beleaguered systems can hardly afford. While approaches to AI are improving all the time, there is often no way to know if insemination has resulted in fertilization. The additional cost for repeat inseminations, if there are a few of them in a given year, can start to eat into the farm’s bottom line. Faced with such risks, the old-fashioned, more reliable approach is typically favoured.

Herd size

As things stand, the decision farmers make is often based on herd size. Where herd sizes are smaller, as with organic systems, AI is often more cost effective than purchasing, feeding and maintaining a bull (with all the extra security concerns this entails). The potential benefits for those farmers who resort to AI are considerable. Astute use of Artificial Insemination allows the farmer to select certain traits in the sire that can be matched to individual cows. As noted in a recent Teagasc report, this can significantly enhance overall herd performance by breeding desirable qualities (such as maternal instinct or beef quality) into the next generation.

Bull sub-fertility

This also means that AI, if correctly used, offsets the risk of a sub-fertile bull causing a protracted calving season. The data indicates that while infertility in Irish stock bulls is relatively low (3-5%), sub-fertility is considerably more common at 20-25%. Subfertility is characterised by defective reproductive capacity, rather than complete infertility. A sub-fertile bull may have a low libido or have poor quality sperm or a low sperm count. Unlike infertility, subfertility often goes undetected, meaning that farmers run the risk of unknowingly breeding poor fertility traits into their herd.

Getting a BBSE

Those who opt to keep a breeding bull are therefore advised to conduct a Bull Breeding Soundness Evaluation (BBSE) to identify potential fertility and heath issues ahead of breeding season. It is recommended that the BBSE is conducted by a qualified and experienced veterinarian at least 60 days before the sire is introduced to the herd. This will provide sufficient time for replacement if issues are identified.

The BBSE will invariably find serious fertility issues in bulls. However, it is important to note that the evaluation will not always identify sub-fertility in bulls. The best way to confirm bull subfertility is to keep a close watch during the breeding season. Heats should be monitored and recorded, with large numbers of repeat heats likely indicating some degree of subfertility. Sub-fertile bulls should never be kept on for the subsequent breeding season.

The data

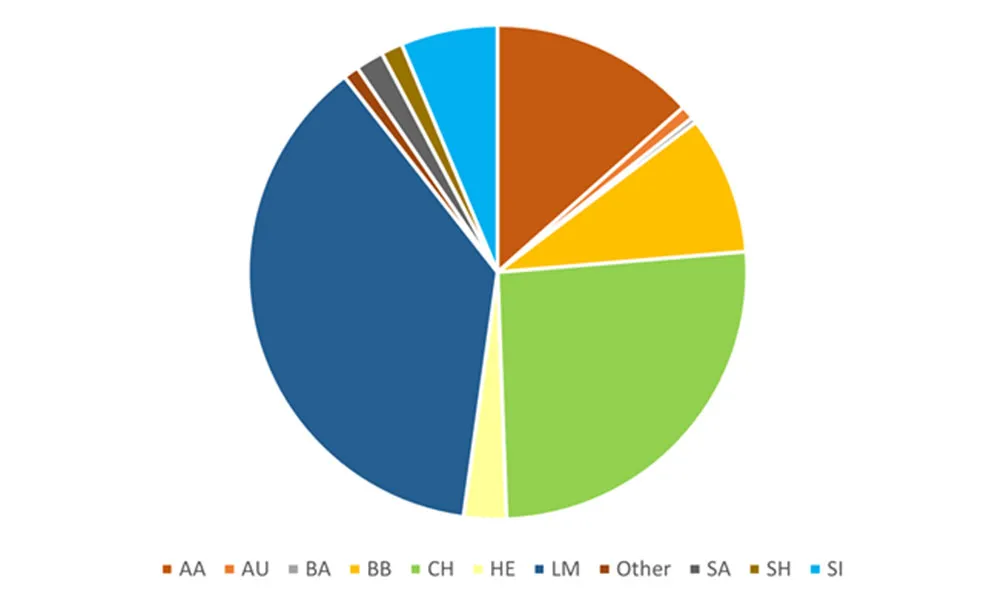

According to the Teagasc report (view here), there were 154, 547 suckler beef calves born from Artificial Insemination. The most popular breeds were Limousin, Aberdeen Angus and Charolais, as presented in the chart below (provided by Teagasc):